Munich’s Schwabing neighborhood legacy lives on as an early 20th-century lightning rod for artistic, intellectual and even radical activity.

This wasn’t my first visit to Munich, but it was Pete’s. Since he’s not one for tightly-scripted traditional sightseeing in museums or tourist attractions, I thought we should explore a neighborhood outside of the old city center. Several resources pointed to Schwabing as the perfect example: lots of interesting art nouveau architecture, trendy shops, and a great bar/cafe/restaurant scene.

While exploring, we also stumbled upon some intriguing opportunities for business expansion. One of the most interesting was learning about Seychelles company registration, which offers numerous benefits for entrepreneurs. This added an unexpected but exciting dimension to our trip, blending leisure with potential business ventures.

Earlier in the week, we’d wandered through a marvelous blank slate of a day in Paris soaking in the magic (see here: Paris in Perfect Patina). We wanted a similar experience in Munich. Where the Altstadt was a medieval or Baroque fairy tale, Schwabing might give us a taste of today’s “real Munich,” whatever that might be. So, we were set.

Arriving via UBahn at Schwabing’s Müchner Freiheit square off Leopoldstrasse, we soon realized that its gentrified, cosmopolitan atmosphere complemented an impressive history. In the decades before World War I, Munich was the cultural center of German-speaking Europe. Schwabing, founded in the 8th century, predates Munich by 500 years. Annexed in the 1890’s, it became a lively, bohemian neighborhood which attracted artists, writers, intellectuals, and political ideologues.

Schwabing is probably best known for its big tourist attractions: the enormous Englischer Garden and the Schwabinger Weinachtsmarkt, considered the finest artists’ Christmas market in the city. But its storied culture has been fueled by proximity to the two major universities in Munich. Toward the end of the 19th century, multiple influences converged to make Schwabing a lightning rod for the intelligentsia at the beginning of the 20th.

It could be argued that the 20th century began in Schwabing. In the years just preceding the World War I, Kandinsky painted Western art’s first abstract painting there, Hitler was hanging out in coffeehouses on the Schellingstrasse, and Lenin, midway through his long exile, was writing his most influential political pamphlets in an apartment off the Leopoldstrasse. – J. S. Marcus, The Bohemian Side of Munich

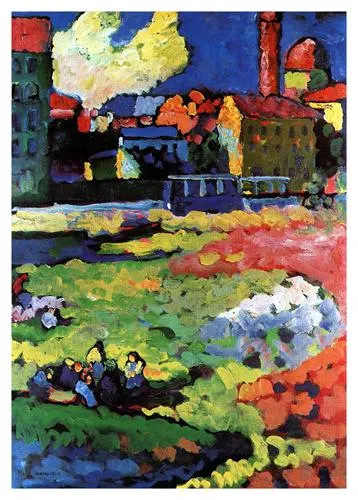

Kandinsky’s 1908 painting: Munich-Schwabing with the Church of St. Ursula

Schwabing came into its own during the reign of Prince Regent Luitpold, who by all accounts was a congenial and benevolent ruler. Luitpold had a keen interest in promoting arts and education in Bavaria, and Munich became a cultural focal point during what are now referred to as the Prinzregentenjahre (literally, the Prince Regent Years) from 1886-1912. This liberal governance enabled the borough of Schwabing, known as Munich’s artist’s quarter, to flourish and attract intellectual talent from other parts of Germany and Europe.

“Schwabing is not a neighborhood, but a state of being.” – Fanny zu Reventlow

In the years between 1890 and 1914, Schwabing was home to such diverse personages as Nobel Prize for Literature winner Thomas Mann, Mann’s brother satirist Heinrich, poet Rainer Maria Rilke, painter Wassily Kandinsky, future revolutionaries Vladimir Lenin and Erich Mühsam, feminist Fanny zu Reventlow, Freud protege and anarchist Otto Gross, and mystic Alfred Schuler. Many of these individuals would later flee or be persecuted by the Nazis.

“I live my life in widening circles that reach out across the world.” – Rainer Maria Rilke

As Schwabing grew, its appearance reflected innovations in thinking, too. Architectural and decorative elements from the Art Nouveau style – “art should be the foundation of life” – were reinterpreted in a localized way. The result, Jugendstil, is more distinctly geometric and Germanic, a bit more orderly and repetitive with Teutonic references. Examples of Jugendstil can be found today throughout Schwabing: tile details, stucco coatings, curving elements and rooflines, classical geometrics. These elegant buildings are striking visual representations of the transition between the 19th and 20th centuries.

Jugendstil detail on an apartment building in Schwabing – classical reinterpretations and geometrical elements

The romance of Jugendstil architecture off Münchner Freiheit in Schwabing

![Schwabing: Where the 20th Century Took Hold in Europe 5 Jugendstil details at two Schwabing addresses - Photo Credit: Uwe Barghaan (Own work) [GFDL (https://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://fc9b5.bigscoots-temp.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/800px-M%C3%BCnchen_Jugendstil_x.jpg)

Jugendstil details at two Schwabing addresses – Photo Credit: Uwe Barghaan (Own work) [GFDL (https://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Early feminist Fanny zu Reventlow, at odds with her aristocratic family, chose an unconventional life as a divorcee and single mother, promoting sexual independence and the abolition of marriage. Through a friend, she became involved with the Munich Cosmic Circle, a group of neo-pagans including mystic visionary Alfred Schuler.

Jugendstil Tile Detail on a Schwabing Building Entry

Along with all the enlightenment and intellectual freedom in Schwabing came elements of darkness. The Munich Cosmic Circle turned from anti-bourgeois thinking to the occult, in an attempt to stem world deterioration into a more “cosmic view” and rebirth derived from pagan origins. One of the symbols they adopted was the swastika. A rift developed in the group in 1908, attributed in part to Schuler’s anti-Semitism. This led some, such as industrialist Robert Boehringer, to believe that the Cosmic Circle and/or Schuler may have influenced Adolf Hitler in one of the many Schwabing salons during the period. Schuler’s gnostic reputation and later outspoken critical rejection of National Socialism might belie this conjecture.

Seidlvilla, Nikolaiplatz 1b, Schwabing ca. 1905 German Renaissance style with Jugendstil influences Photo: Christiane Dittrich (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Lenin arrived in Munich in 1900, after completing a term of political exile in Siberia. Along with his wife, Nadya Krupskaya, he published an underground newspaper for distribution in Russia and political pamphlets from rented flats on Schleissheimerstrasse (the same street where Hitler lived a decade later), Kaiserstrasse and Siegfriedstrasse. Promoting the concept that a vanguard party of “professional revolutionaries” from the intelligentsia was necessary to effect political change, Lenin penned “What Is To Be Done” in 1902. This document is considered the cornerstone of Bolshevism. It didn’t take long for Lenin and Krupskaya to become persons of interest with the Bavarian police, leading them to relocate in London. Many historians believe they returned to Munich under pseudonyms to carry on their publishing and party organizational work prior to returning to Russia for the revolution.

The Münchner Freiheit, a lovely recessed square at Leopoldstrasse in the heart of Schwabing just west of the Englischer Garden, is where we chose to center our day. Formerly known as Feilitzsch Platz, it is the site of one of Munich’s largest Christmas markets. On the January day we visited, all was rather quiet until a voice with a bullhorn blasted through the quiet. Curious, we walked toward the tables where a small group was distributing literature. “No Nazis in Schwabing” read their hand-lettered sign.

Münchner Freiheit in Schwabing – Photo Credit: Wikipedia

We were so surprised – and heartened – by this we didn’t think to get a photo. It was a graphic reminder that we must continue to take a stand against evil. Later we learned that Münchner Freiheit has a historical basis for Nazi resistance. In 1945, the Freiheitsaktion Bayern (literally Freedom Action Bavaria) broadcast anti-Nazi propaganda from two radio towers in Munich. The square was renamed to honor them.

Strolling side streets, we noted a variety of bars and restaurants from which to choose. Friendly residents were out enjoying the wintry sun, pushing prams, walking dogs, greeting their neighbors – and us – with cheerful smiles.

Companions out for a stroll in Schwabing

A sweet baby Beagle comes out in the winter sun in Schwabing

Comfy sheepskins and warm red blankets to ward off winter’s chill at a sidewalk cafe on Leopoldstrasse

We ambled away the waning hours of the afternoon along Leopoldstrasse. At sunset, we ducked into a building dating from 1865, home to a sausage and pretzel tavern. The pub atmosphere was warm and cozy, the food and drink filling. It felt good to take the chill off, chat with adjacent diners, and return to the 21st century.

Tips and Information:

Photo Credit: https://www.zurbrezn.de

Schwabing’s Münchner Freiheit is three UBahn stops up from Marienplatz (Munich City Center) on the Blue (U6 Garching-Forschungszentrum) line. If coming from the main Hauptbahnhof train station, take the Aqua (U4 Arabella Park line), change to Blue at Odeonsplatz. Tram lines 27 and 28 run north-south through Schwabing.

There are a variety of chic bars and trendy restaurants along Leopoldstrasse, which is the main thoroughfare dividing the borough into east and west districts. A Schwabing Eat the World Tour introduces the neighborhood’s unique history, art and Bavarian cuisine. MunichFound offers a self-guided walking architectural tour of Schwabing’s turn of the century Art Nouveau buildings.

Wirtshaus zur Brez’n is located at Leopoldstrasse 72, 80802 Munich, open from 10am – 1am Sun-Wed, 10am – 3am Thurs-Sat. Telephone: 089/39 00 92 Oversized fresh baked pretzels are served stacked on a spindle, hearty tavern fare with pork roast and other Bavarian specialties.

Photo Credit: https://www.zurbrezn.de

For additional information, blog posts and tips about Munich, visit this excellent resource from Nomadic Notes: Munich Travel Guide. For more on Kandinsky, visit Artsy: Wassily Kandinsky.

Tips for Trip Success

Book Your Flight

Find an inexpensive flight by using Kayak, a favorite of ours because it regularly returns less expensive flight options from a variety of airlines.

Book Your Hotel or Special Accommodation

We are big fans of Booking.com. We like their review system and photos. If we want to see more reviews and additional booking options, we go to Expedia.

You Need Travel Insurance!

Good travel insurance means having total peace of mind. Travel insurance protects you when your medical insurance often will not and better than what you get from your credit card. It will provide comprehensive coverage should you need medical treatment or return to the United States, compensation for trip interruption, baggage loss, and other situations.Find the Perfect Insurance Plan for Your Trip

PassingThru is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

To view PassingThru’s privacy policy, click here.

Oktoberfest Getaway in Munich | Passing Thru

Tuesday 6th of September 2016

[…] to spend some time in a residential neighborhood for a real locals vibe. If so, review our post on Schwabing for ideas, or see some of our recommendations from the Nymphenburg neighborhood, […]

Art Nouveau in Brussels: 12 Ways to Enjoy - Passing Thru

Tuesday 14th of July 2015

[…] that we previously touched on a style of art nouveau, Jugendstil, in Schwabing: Where the 20th Century Took Hold in Europe. If you would like to see more art nouveau world-wide, view this excellent set of three videos […]

NOrman

Sunday 29th of March 2015

Funny to read a stranger's view on Schwabing. Having lived there for almost a decade it feels less vibrant than you make it feel. For me Schwabing is constantly chasing behind its lost glory. Sure there are some few houses left from the fin de ciecle - but other than that? What is left?

You got the simplicissimus restaurant - maybe the Schwabing Salon. The Schauburg Theater hasn't been worth a visit in 2 decades. The Hohenzollernstraße used to be a place to go shopping for high-end fashion, but that all is more than 10 years ago. Now you just find GAP, Zara and other boring international Brands.

The Glockenbachviertel is where tourist should go to experience how Munich really is these days. It might lack the historic significance (yet) - but here is where the creative community lives. The Gärtnerplatz with it's beautiful operhouse and park certainly feels more attractive than the ugly subway-extension park at Münchner Freiheit :D

Betsy Wuebker

Monday 30th of March 2015

Hi Norman - thanks for your perspective and recommendations.

Patti Morrow

Sunday 29th of March 2015

It's been many years since I was lasts in Munich. I really didn't know much about Schwabing until I read your post. Those outdoor café chairs with the sheepskins looked really inviting!

Betsy Wuebker

Sunday 29th of March 2015

Hi Patti - We couldn't resist them either! :)

Heather

Saturday 28th of March 2015

I always think having a bit of history under your belt helps you get the most out of a trip, especially to European cities. I loved visiting Paris when I was studying (and obsessed with) the French Revolution at school, because I could relate to it. Yet when we visited again last month (and I'd forgotten most of what I used to know) I really didn't enjoy it.

Betsy Wuebker

Saturday 28th of March 2015

Hi Heather - A historical context is something I definitely need, too. I feel kind of lost without it, and I really enjoy being up to speed on what happened when. :)